Protest and Video art

Cinematic art in its intrinsic nature has always been transgressive. Back when Dziga Vertov first introduced the world to the kino-eye, cinema was already pushing the boundaries of perception and representation, or even, what it even is to perceive and to play a part. What Vertov did was not just film, he was rethinking vision itself, reshaping the process by which we witness the world, and in doing so, became the precursor to something even bigger — the notion that art can be an act of intervention.

Filming, capturing videos became a tool for resistance, a way to challenge the status quo by altering the very systems through which the world is shown to the audience. To subvert the norm.

'Possession', Andrzej Żuławski, 1981. Protest against the female status-quo, motherhood and the instituions of marriage.

When one talks about 'protest' in motion art, even though it still remains an act rooted in politics, but rather than social politics or economic crises we often hear about on various social media, one should turn their gaze to an identity. Protest in video art is a deeply personal confession, a conflict of personal interests and consequences of what we most often cannot control.

Protest in video art is a radical redefinition of how we see, record, distribute, communicate and cope — a rejection of those norms enforced on both the creators and the audience by figures in power and the status-quo.

'Mulholland Drive', David Lynch, 2001. A protest againts the American film industry, Hollywood, and explotation of art for money.

By disrupting the typical logic of representation — the clean lines of narrative, the comforting certainty of the frame, the ease of social and cultural codes — video artists expose the cracks in the foundation of how we understand the world.

Susan Sontag in her work 'Regarding The Pain Of Others' poignantly points out that images are never neutral. Every act of seeing is inherently political, and something is always shown to us for a reason: blockbuster movies, box office action slop with A-list celebreties, Oscar-baits, giving illusion of a message that in reality doesn’t stand the test of dissecting. To witness is to interpret, to question, to potentially resist; and to record, to act, to publish, to put one’s art out there is always to spread a message. In this visual research, we will be looking in just what ways videoart dares to protest, not to conform.

To film is to protest. To watch is to resist.

Contents

1. Concept 2. Subverting The Format and Interpretation 3. Media, Censorship, Commerce 4. On Social Commentary and Oneself 5. Conclusion

Subverting The Format. The viewer’s Interpretation and the creator’s perspective

Back when the term 'videoart' wasn’t as widely used, the medium was emerging as a mere subversive experiment. This was the era when Fluxus, an international network of artists, introduced a new approach to art. Fluxus was a movement that sought to blur the lines between art and life, emphasizing interactivity, playfulness, and democratization of art. The group encouraged artists to experiment with new media and techniques, incorporating elements from sound, performance, and even everyday objects into their works, always with the intention of subverting the viewer’s expectations and redefining what art could be.

Nam June Paik, Zen For Film, 1964.

In the case of Paik, video became a powerful medium for disrupting not just artistic conventions, but the very way in which viewers engaged with moving images. Create interaction where it once sought to be impossible to appear. His 'Zen For Film', a 7-minute long white video with film grain, is, perhaps, an ultimate dare to what videoart can be. Everything the viewer wants it to become, but almost nothing without its audience.

Nam June Paik, Zen For Film, 1964. Framed as it was shown at exhbitions.

Yoko Ono’s work, a fellow member of the Fluxus Foundation, followed in Nam Joon Paik’s footsteps in experimenting with the medium and the technologies. Singular angles, slow-motion and rapid shots, often times playing with themes of body, nudity and life.

Eyeblink, Yoko Ono, 1966 and No.4 (Bottoms), Yoko Ono, 1967.

One Stroke of Painting (still), Kim Soun-Gui, 1975-1985.

One Stroke of Painting (still), Kim Soun-Gui, 1975-1985.

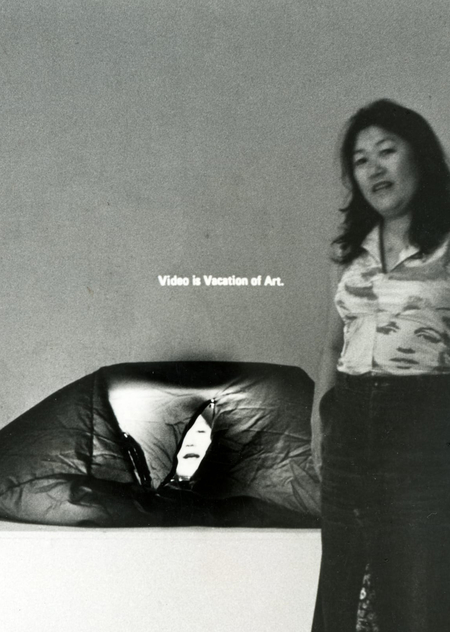

Among other pioners are Kim Soun-Gui, who found videoart a 'primal' and raw tool for executing visual metaphors; as well as Shigeko Kubota, who used video to create diaries of her work, infuse them with voice over and editing tools. Videoart opened a portal for art to become multidisciplinary — interactive, cinematic, poetic.

Video Poem, Shigeko Kubota, 1970-1975.

'Video Is Vacation of Art' — Shigeko Kubota.

Video Poem, Shigeko Kubota, 1970-1975.

Censorship, Commerce, Surveillance

As a medium devoid of ways to commercialize itself, it only makes sense for videoart to stand agains the industry. While mainstream cinema and mass media often operate within commercial frameworks, designed for profit, mass consumption, and mass appeal, video art has historically been a space for critique and nuance.

Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, Dara Birnbaum, (1978-1979).

'Dara Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman' (1978-1979) stands as a powerful critique of both media representation and the gendered politics of the popular in mass media superhero genre. Using footage from the television show 'Wonder Woman', Birnbaum dismantles the traditional portrayal of the female superhero and exposes the underlying patriarchal commercial structures that disguise themsevles as female empowerement.

Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, Dara Birnbaum, (1978-1979).

Videoart allows for reframing and reimagining. It can take something pre-existing and turn it against itself, make it the example in the discourse without adding anything extra or new, except for one thing — context.

Videoart fights what it stand againts by showing, not telling. Videoart rarely explains — it expects the viewer to derive meaning from observing footage through lenses of cultural and ideological context. Videoart needs the viewer to agree with it, or at least understand its point of view.

A work by Barbara Kruger gave birth to a now infamous phrase: 'Your body is a battleground'. Barbara Kruger addresses media and politics in their native tongue: tabloid, sensational, authoritative, and direct. Kruger’s words and images merge the commercial and art worlds; their critical resonance eviscerates cultural hierarchies — everyone and everything is for sale.

Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground), Barbara Kruger, 1989. Installation and video.

Fast-forwarding to 2013, the issue of representation still stands. Why are certain people given fame, why do some become idols, while others remain unheard and invisible? Why are narratives twisted and exploted for commerce? But most importantly — why is the viewer not the one behind the camera? Has he nothing to say in the era of mass media?

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, Hito Steyerl, 2013.

Artist and critic Hito Steyerl’s video works delve into the ways in which images are created, circulated, and consumed. Steyerl has described images as a 'condensation of social forces' implying that through these visual representations, we can uncover and trace the hidden systems and power structures that shape our contemporary world.

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, Hito Steyerl, 2013.

In her words, 'How do people disappear in an age of total over-visibility? . . . Are people hidden by too many images? Do they go hide amongst other images? Do they become images? '

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, Hito Steyerl, 2013.

On Social Commentary and Oneself. Violence, values, the government and the citizen

Videoart gave an opportunity to the marginalized and the unheard — seize the power and shift the discourse. For many artists, videoart became a platform for sociopolitical engagement, where they could address injustices, challenge cultural stereotypes, and engage with issues of identity, race, gender, and power — something mostly looked down upon by the status-quo institutions of art. Artists like Martha Rosler, Barbara Kruger, and Valie Export used video to expose the violence and oppression that was often invisible in the mainstream media, confronting the viewer with uncomfortable truths and offering their version of the truth, uncovering what remained hidden.

Dance, Albert Fine, 1966. Shadowboxing.

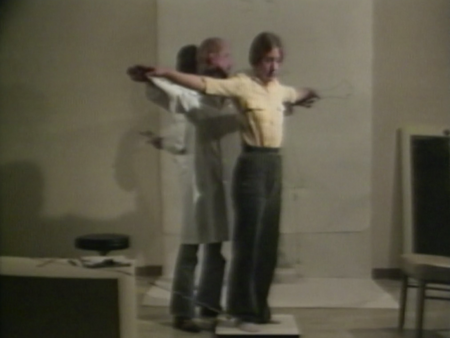

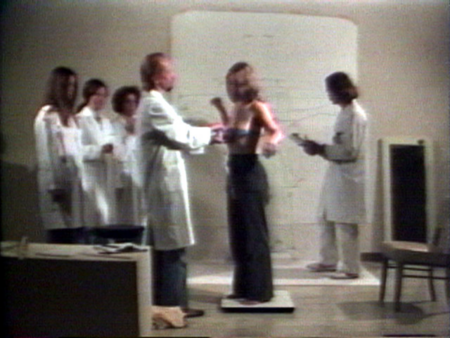

Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained, Martha Rosler, 1977.

Martha Rosler takes direct aim at the social standardization imposed on women’s bodies, critiquing the politics of 'objective' or scientific evaluation that leads to the depersonalization, objectification, and colonization of women and marginalized groups. As Joseph Di Mattia astutely observes, 'The title of the tape is ironic—just exactly to whom are these 'statistics' 'vital'? They are vital to a society that defines and restricts the roles and behavior of women.» Rosler positions the female body as the battleground of an ideological struggle, where it becomes the site of physical domination that degrades, diminishes, and subjugates women. Through her work, she reveals how women’s bodies are not only subjected to external control but are also manipulated by societal forces that strip them of agency, rendering them as objects to be measured, dissected, and controlled.

Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained, Martha Rosler, 1977.

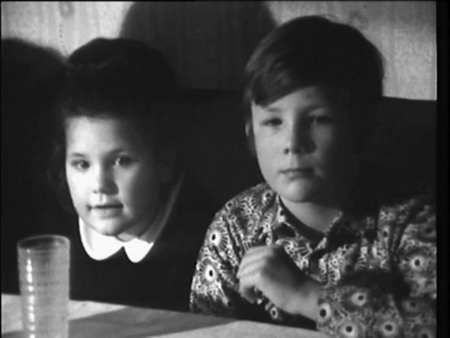

Facing a Family, Valie Export, 1971.

In 'Facing a Family', Export examined the social implications of mass media and its influence on cultural norms, especially concerning family values. The video interrogates how television, as a tool for mass communication, was becoming the central medium for shaping ideas of the ideal family life, while also predicting contemporary issues such as online surveillance and the growth of reality television, both of which continue to perpetuate a voyeuristic, commercialized view of family life.

In this work, the nuclear family is not presented as an idealized image, but as something to be critically observed, almost dissected, made fun of.

Facing a Family, Valie Export, 1971.

Milica Tomic in her 'I am Milica Tomich' particularly explores theoretical consequences of identification. In one and the same process this work questions both paranoiac spaces of particular national identities (leading to xenophobia, discrimination, violence) and hysterical spaces of new globalization (representational over excitation that turns the world into image).

I Am Milica Tomich, Milica Tomich, 1999.

I Am Milica Tomich, Milica Tomich, 1999.

As she continues on with different languages, lacerations appear and multiply on her body. The lacerations act as a metaphor for the violence inflicted upon self in the act of translation, where each shift in language cuts deeper into the fabric of who we are, revealing the underlying tensions of cultural displacement, immigration and international politics.

I Am Milica Tomich, Milica Tomich, 1999.

Tomich protests against borders, against governments that make connecting with one’s cultural identity so painful and sometimes even punishable by the masses. There’s a lack of immediacy — we don’t see how those wounds appear or who inflicts them. They appear gradually, marking the very personal nature of the consequences of events that are far beyond a single individual’s reach.

Territories, Isaac Julien, 1984.

At last, videoart can protest not figuratively, but literally — yet again, simply by showing and documenting.

Territories, Isaac Julien, 1984.

In Territories, Julien creates a cinematic space where the tensions between personal experience and broader cultural forces are made visible, especially through the lens of marginalized voices. The video examines the lives of Black, queer men in London, using their experiences as a microcosm for larger societal and political issues. It reflects how the politics of identity, shaped by race, sexuality, and class, are embedded in everyday life, and how these identities become sites of protest, resistance, and sometimes violence.

The work itself is a collage of images that speaks to the fragmented and multiplicative nature of identity. In the same way that video art often disrupts linear narratives and challenges traditional representation, Julien uses non-linear editing, sound, and visuals to destabilize the viewer’s understanding of race, class, and sexuality, refusing to allow a singular narrative to dominate.

Territories, Isaac Julien, 1984.

Videoart can go beyond simply representing protest, spreading a message or subverting a norm — the entire act of filming, framing and editing can be a protest in it of itself.

Conclusion

Video art stands as a resounding testament to the power of vision—not just as a passive act of observation, but as a form of resistance, a deliberate, transformative force. It is in this space, where identity meets power, that video art finds its truest expression of protest.

Through the lens of video art, we are reminded that protest is not merely an act of resistance against the powers that oppress us; it is an act of rebirth, of reclaiming the very systems of representation, of challenging the comfortable narrative that the world forces upon us. In disrupting the familiar, video art forces us to see, to question, and ultimately, to resist. The artists we’ve explored here have not just made videos; they’ve ignited a movement of vision, a radical shift in how we understand what it means to be human, to be seen, and to be free. In their work, they remind us that art, at its core, is always an act of intervention.

Videoart is a refusal to accept the world as it is, and a bold declaration asking us only but to observe, interpret and make change.

The BROAD [WEB] —. URL: https://www.thebroad.org/art/barbara-kruger/untitled-your-body-battleground

Artbasel [WEB] —. URL: https://www.artbasel.com/news/three-female-pioneers-artists-from-asia-forefront-video-art-revolution-art-basel-hongkong?lang=en

VDB [WEB] —. URL: https://www.vdb.org/titles/vital-statistics-citizen-simply-obtained

MoMA [WEB] —. URL: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/181784

YouTube. Vital Statistics of A Citizen [WEB]. — URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b91_vZ8TauM: (09.11.2025)

YouTube. Your body is a battleground [WEB]. — URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkozdO4W4Zs: (18.11.2025)

YouTube. 1971 Valie Export Facing a Family [WEB]. — URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUjdINipz_A: (12.11.2025)

YouTube. Dara Birnbaum’s 'Technology [WEB]. — URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wJhEgbz9piI: (16.11.2025)

YouTube. How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational [WEB]. — URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LE3RlrVEyuo: (04.11.2025)

I am Milica Tomic [WEB]. — URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1kagFMbQ5k: (02.11.2025)

Vk.com. Territories (1984) Isaac Julien [WEB]. — URL: https://vk.com/video642792594_456239966: (10.11.2025)

Instagram. Shigeko Kubota, video poem (1970-1975) [WEB]. — URL: https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1F_xGwO2iA/ (10.11.2025)

Arario Gallery. Meet Asia’s female video art pioneers [WEB]. — URL: https://www.arariogallery.com/artworks/9601-kim-soun-gui-one-stroke-of-painting-1975-1985/ (16.11.2025)

UBU. Flux Film Antology. [WEB]. —URL: https://www.ubu.com/film/fluxfilm.html (16.11.2025)